THE BOBBY ROBSON I KNEW AND LOVED

On 31 July 2009, the day Sir Bobby died, his friend George Caulkin wrote this tribute to him.

George is Northern Sports Correspondent of The Times and a Patron of the Sir Bobby Robson Foundation.

To the end, he carried with him a sense of enchantment; wonder that life had offered him such a rich experience, disbelief that people should love him and venerate him in the way they did. If it was not for the physical manifestations, you would never have known that illness had touched him, because Sir Bobby Robson was not defined by the cancer growing inside him. He was defined by energy, enthusiasm and curiosity. By enchantment.

To the end, he carried with him a sense of enchantment; wonder that life had offered him such a rich experience, disbelief that people should love him and venerate him in the way they did. If it was not for the physical manifestations, you would never have known that illness had touched him, because Sir Bobby Robson was not defined by the cancer growing inside him. He was defined by energy, enthusiasm and curiosity. By enchantment.

There were flashes of frustration when the frailty of his body prevented him from driving, or playing golf or tending to his garden, but questions about his health would invariably meet with the same response. “I’m all right,” he would say. “I’m all right.” And then, with barely a pause, he would manoeuvre the conversation towards its inevitable destination. “So what’s happening at Newcastle, then?”

Perhaps it was courage or perhaps it was a by-product of his age and upbringing among Co Durham mining stock. Or perhaps it was just some sorcerer’s life-affirming quality that could persuade the eyes and brain that they were being deceived. Yes, he looked poorly, yes, he was grappling with a fatal disease, but no, it would not claim him. He had an aura of indefatigability. Whatever the evidence, we thought he was invincible.

Spend time in his company and you grasped why all those footballers revelled under his leadership. Take away the nous, the years of accumulating tactical knowledge, his technical qualities as a coach and manager and you were left with an expansive personality that illuminated its surroundings. When you walked away, a bit of his sparkle clung on. It was the quality of a talisman, an Everyman.

Flags were at half-mast at St James’ Park yesterday, just as they were at the Stadium of Light, the home of Sunderland, Newcastle United’s great rivals. Red-and-white shirts mingled with black-and-white in the ground Robson first visited with his father during the Second World War and which was opened to allow supporters to pay their respects. The sun at lunchtime was warm and blissful and the grass a tempting shade of green. Pull your boots on, son.

Tyneside has witnessed much disillusion and despair in recent months, but this was different. You could feel the history, hear the echo of past glories. Looking across the turf towards the Gallowgate End, the head spun tipsily at the expanse of dynamic space, where not all that long ago, Robson’s team had graced the Champions League. It felt like a football club. Finally, once again, it felt like a football club.

Families sat in the Leazes End engrossed in quiet contemplation. A woman in a Middlesbrough top gazed at the banks of scarves and shirts that had been looped around seats. Just as Sir Bobby straddled the generations — he had watched Albert Stubbins and worked with Alan Shearer — he was a unifying figure, of his region and also far beyond it. Here was proof, in monochrome and colour.

There had been more last Sunday and in the same place, when 33,000 people had defied the financial and, in Newcastle terms, sporting recession to watch a friendly match between England and Germany, organised to benefit the Sir Bobby Robson Foundation and in honour of its patron. It had been a near thing, but Robson had made it, receiving a tumultuous reception as he was pushed around the pitch in a wheelchair.

Robson fulfilled his final fixture, just as against the advice of his family and doctors, he had fulfilled a commitment to attend his own annual charity golf day in Portugal a few weeks ago. Those closest to him made their arguments, rolled their eyes and ultimately accepted what they always knew: he would not be told. Not when he had given his word, not when he had a challenge to complete. Call it principled stubbornness.

You do not get to where Sir Bobby got — to England, to Barcelona, to the Premier League — without sharp elbows, without necessary hardness, but he maintained his dignity, his relish and warmth. He inspired loyalty and adoration because his spirit was both real and transferable. It rubbed off. He felt and nurtured passion, for football, for Newcastle, for hard work, for the goodness in people, for life.

You do not get to where Sir Bobby got — to England, to Barcelona, to the Premier League — without sharp elbows, without necessary hardness, but he maintained his dignity, his relish and warmth. He inspired loyalty and adoration because his spirit was both real and transferable. It rubbed off. He felt and nurtured passion, for football, for Newcastle, for hard work, for the goodness in people, for life.

His achievements in the sport are detailed elsewhere and so, too, are the wider responses to his death, but, even so, please excuse the personal nature of what follows. It is an attempt to contextualise, but also to explain the reactions Sir Bobby could dredge from you, even in a profession such as this one, where cynicism is often rampant. It is also something else: a love letter.

When I joined The Times as their North East football writer in 1998, Robson was a contributor to the newspaper. He was a hero of mine; I’d followed him to Langley Park infants school and, like him, supported Newcastle. When he was appointed as the club’s manager the next year, Oliver Holt, who then ghost-wrote his column and is now the Daily Mirror’s respected chief sports writer, bequeathed the task to me, an act of journalistic generosity that leaves me indebted for several lifetimes.

A relationship would develop, but initially it was about getting a story, pressing him for news, for stronger comments, predominantly about England. But over time and without noticing, the parameters shifted. Listening to him speak and putting his thoughts into words provoked different motivations. I wanted to do him proud and make him proud. I wanted my efforts to be worthy of him.

It was not such an onerous challenge, because his voice was so distinctive, his turn of phrase so lyrical — although I remember one telephone conversation we had, up against the paper’s deadline, when he was simultaneously talking to Lady Elsie, his wife; he kept calling her “son” and me “love” — but it did not often happen that way.

Few people, never mind football people, make you operate solely from the heart. Last year, he asked me to assist him with a book about Newcastle — the city and the club. Even the request made me weep. It also prompted fear, not only because his autobiographies had been written so beautifully, but because it would form part of his legacy. To call it the proudest, happiest and most terrifying episode of my career is a gross understatement.

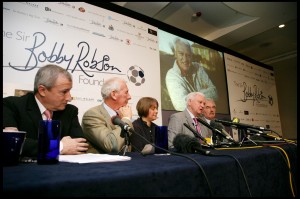

Over the course of last summer, we met regularly at the Copthorne Hotel on Newcastle’s quayside, or at his home in Urpeth, Co Durham. Usually accompanied by Judith Horey, Sir Bobby’s wonderful, longstanding personal secretary, we would sit and chat about his childhood, the memories of Stubbins and Jackie Milburn, his first job down the pit. It was an extraordinary privilege.

The final chapter of Newcastle, My Kind of Toon centred on Sir Bobby’s lengthy tussle with cancer and how it inspired him to establish the foundation that bore his name. “I’ve had a great life, I really have,” he wrote. “When I look back on everything I’ve done and seen, the experiences I’ve had, the myriad colours and memories, I don’t feel as though I’ve ever been ill.

The final chapter of Newcastle, My Kind of Toon centred on Sir Bobby’s lengthy tussle with cancer and how it inspired him to establish the foundation that bore his name. “I’ve had a great life, I really have,” he wrote. “When I look back on everything I’ve done and seen, the experiences I’ve had, the myriad colours and memories, I don’t feel as though I’ve ever been ill.

“I’ll puff out my chest and say to Elsie, ‘I’ve been fit all my life, I have’. She’ll look at me as if I’m daft. ‘Bobby, what are you talking about? You’ve had cancer five times’. She’s right, of course, but it rarely interrupted my work and never detracted from my enjoyment of living. If you’re 2-0 down at half-time, what do you do? You look at where the game is going wrong and why and what you’re going to do about it.”

The Foundation has raised more than £1.6 million for anti-cancer projects under the NHS banner (today, £7.3 million), including a specialist research centre at Newcastle’s Freeman Hospital. As ever, the messages from donors were humbling: “You were an inspiration to so many, a true local hero. Rest in peace Bobby”; “Always smiling, passionate and a true gentleman, a credit to England & the world of football”; “In memory of Bobby and my dad”; “My grandad has started treatment at the Freeman. He is very similar to Sir Bobby — a kind-hearted Geordie”.

Typically, he was uncomfortable about the use of his name, that it somehow suggested arrogance. “Why would people want to give money to me?” he said. The answer came not only in the big cheques from powerful friends, but when he went to matches at Newcastle, Sunderland or the Riverside Stadium and left with his pockets bulging with £5 and £10 notes, given by those who could afford no more.

He threw himself into it. Behind the scenes, the likes of Lady Elsie, Judith and Liz Luff, the one-woman publicity machine, toiled assiduously for the foundation, but it would have been worthless without Robson’s determination to drive it forward, even when the news about his own wellbeing was dispiriting and, later, calamitous. He would not miss meetings or engagements, he could not contemplate letting people down.

He threw himself into it. Behind the scenes, the likes of Lady Elsie, Judith and Liz Luff, the one-woman publicity machine, toiled assiduously for the foundation, but it would have been worthless without Robson’s determination to drive it forward, even when the news about his own wellbeing was dispiriting and, later, calamitous. He would not miss meetings or engagements, he could not contemplate letting people down.

Self-pity was never an issue and neither, amazingly, was bitterness, in any aspect of his existence. His departure from Newcastle in 2004 was a source of anger, but that quickly faded, even as he watched the club he rebuilt unravel so disastrously. You can get dizzy searching for turning points at Newcastle, but Sir Bobby’s dismissal equated to a moment when soul was lost and respect dissipated.

But hate withered inside him; it had no fertile ground on which to grow. Instead, he reverted to his youth, travelling from Urpeth to St James’ when his health allowed, black-and-white scarf around his neck, relishing the occasion and the atmosphere. As things grew worse, he felt only sadness. When you relayed the latest gossip — usually negative — he would tut and shake his head, but he was forever optimistic.

He was eager for Shearer or, before he accepted the same post at Sunderland, for Steve Bruce to be appointed Newcastle’s next permanent manager; like him, they understand the rhythms of the North East, the yearning, the pride, the special, crazy beauty. Bruce was among the men who travelled to Sir Bobby’s home on Thursday for a last and quiet farewell.

Yet, despite the circumstances, solemnity does not quite fit. “Cancer takes no account of colour — black-and-white or red-and-white, orange or purple, young or old, male or female, weak or strong, we’re all the same,” the old pitman wrote in My Kind of Toon. “I’m desperately proud that a facility in Newcastle, my city, my father’s city, the city where football burrowed deeper into my body than any disease ever could, will bear my name, but more than that, I’m honoured and touched by the response our appeal has had across the region and beyond. Yes, I was born into a black-and-white world. But as my last great challenge draws to a close, I am more convinced than ever that we are surrounded by light, not darkness.”

Robson would have been touched by yesterday’s release of emotion; touched, embarrassed and faintly quizzical. Are they talking about me? He would have loved the warm words from football men such as Sir Alex Ferguson and Niall Quinn and he would love it even more if Newcastle could scrape a victory away to West Bromwich Albion next Saturday. He would have loved the cricket score, too.

Robson would have been touched by yesterday’s release of emotion; touched, embarrassed and faintly quizzical. Are they talking about me? He would have loved the warm words from football men such as Sir Alex Ferguson and Niall Quinn and he would love it even more if Newcastle could scrape a victory away to West Bromwich Albion next Saturday. He would have loved the cricket score, too.

Apologies are due, again, because this has been a rambling, incoherent sort of tribute — although I hope I’ve got the names right — and Sir Bobby did not take kindly to slackness. There was so much I wanted to tell him, to thank him for, to explain how it felt to be near him, to listen to, to appreciate and learn. He has gone now, but the same feeling lingers: I’m still desperate to make him proud.

Reproduced by permission of George Caulkin and The Times

Sir Bobby was the most loveliest man I had ever met, even an hour before the West Brom game in 2002, he still had time to sign my programme. He was a true gentlemen and that was a proud moment for me. I shouted “Alreet Bobby!?” To then my dad to correct me by saying ” SIR Bobby” for which Sir Bobby to say “Bobby will just do”. He never let the fame get to his head. Again the most lovely man I had ever met. R.I.P Sir Bobby, true Geordie legend x

Thanks George,

It all came flooding back as I have been with Charlie today, (Footballer, not my Dog!)

Good article, thanks.

A’